Negli anni ’60, Los Angeles non era semplicemente una città: era una fornace culturale, un crogiolo di tensioni, sogni e rivoluzioni. Le sue strade brillavano di inquietudine, popolate da giovani in cerca di un altrove, immersi in un’atmosfera fatta di luci al neon, fumo dolciastro, guerra trasmessa in TV, amore libero e psichedelia. In quell’aria sospesa aleggiava una domanda che nessuno osava ignorare: “Dove stiamo andando?”

In questo scenario emerse Jim Morrison, nato l’8 dicembre 1943 a Melbourne, Florida, in una famiglia militare rigidamente disciplinata. Suo padre, George S. Morrison, sarebbe diventato contrammiraglio della Marina degli Stati Uniti. L’infanzia di Jim fu segnata da continui trasferimenti , Florida, Virginia, Texas, Nuovo Messico, California , che lo privarono di radici stabili ma alimentarono un immaginario in costante movimento. Secondo il suo racconto, un episodio avvenuto all’età di circa quattro anni lo segnò profondamente: un incidente stradale nel deserto, in cui un camion di nativi americani si era rovesciato. Guardando la scena, disse, “gli spiriti degli indiani entrarono in lui”. Questa immagine, reale o simbolica, divenne uno dei suoi miti personali, ricorrente nei testi e nelle poesie.

A scuola mostrava un’intelligenza vivace, anticonvenzionale, spesso provocatoria. Amava Dostoevskij, Huxley, Rimbaud, Nietzsche. Scriveva appunti criptici, frasi spezzate, riflessioni sui margini dei quaderni. La famiglia, di stampo militare, faticava a comprenderne i lati artistici e ribelli. A 17 anni si trasferì a vivere da solo, rompendo gradualmente i contatti con i genitori.

Dopo aver frequentato la St. Petersburg Junior College e la Florida State University, Morrison approdò alla UCLA, dove studiò cinema. Fu lì che la sua personalità artistica acquisì una struttura più definita. Divorava film e poesia: Cocteau, Fellini, Artaud, i surrealisti francesi, Ginsberg, Kerouac. Iniziò a sviluppare uno stile di scrittura visionario e non lineare, intriso di simbolismo, erotismo mistico, fascinazione per la morte come passaggio e metamorfosi, introspezione psicologica quasi sciamanica.

In the 1960s, Los Angeles was not merely a city, it was a cultural furnace, a crucible of tension, dreams, and revolution. Its streets shimmered with restlessness, teeming with youth in search of an elsewhere, immersed in an atmosphere of neon lights, sweet smoke, televised war, free love, and psychedelia. In that suspended air lingered a question no one dared to ignore: “Where are we going?”

It was in this setting that Jim Morrison emerged, born on December 8, 1943, in Melbourne, Florida, into a strictly disciplined military family. His father, George S. Morrison, would become a Rear Admiral in the United States Navy. Jim’s childhood was marked by constant relocations, Florida, Virginia, Texas, New Mexico, California, which deprived him of stable roots but fueled a constantly shifting imagination. According to his own account, a formative episode occurred around the age of four: a desert car accident involving a truck full of Native Americans. Watching the scene, he said, “the spirits of the Indians entered him.” This image, whether real or symbolic, became one of his personal myths, recurring in his lyrics and poetry.

At school, he displayed a lively, unconventional, often provocative intelligence. He loved Dostoevsky, Huxley, Rimbaud, Nietzsche. He scribbled cryptic notes, fragmented phrases, and reflections in the margins of his notebooks. His military-style family struggled to understand his artistic and rebellious sides. At 17, he moved out on his own, gradually severing ties with his parents.

After attending St. Petersburg Junior College and Florida State University, Morrison arrived at UCLA, where he studied film. It was there that his artistic personality took on a more defined shape. He devoured cinema and poetry: Cocteau, Fellini, Artaud, the French surrealists, Ginsberg, Kerouac. He began to develop a visionary, non-linear writing style, steeped in symbolism, mystical eroticism, a fascination with death as passage and metamorphosis, and a near-shamanic psychological introspection.

Trascorreva gran parte del tempo in solitudine, camminando per Venice Beach, scrivendo versi sui taccuini, vivendo di cibo e vino economico. Nel 1965, dopo il diploma alla UCLA, si allontanò dalle cerchie universitarie. Fu su una spiaggia di Venice che Ray Manzarek lo incontrò e gli chiese cosa stesse facendo. Morrison rispose che scriveva poesie. Quando lesse alcuni versi — “Let’s swim to the moon / Let’s climb through the tide…” — Manzarek rimase folgorato dalla musicalità naturale della sua voce. Così nacquero i Doors. Per Morrison, la musica divenne il mezzo per trasformare la sua poesia in esperienza rituale collettiva.

A loro si unirono Robby Krieger e John Densmore. Krieger, chitarrista dall’anima gentile, era influenzato dal flamenco, dal blues e dalla musica indiana. Densmore, batterista jazz, era preciso, introspettivo e spirituale. La chimica tra i quattro fu immediata. Morrison portava la visione e la voce come un tempio sotterraneo; Manzarek la struttura, con un organo che diventava orchestra e incenso; Krieger il sentimento, con una chitarra liquida e scorrevole; Densmore il ritmo del cuore, con battiti tribali e sincopi jazz. Nessuna band suonava così.

Il loro primo palco fu il London Fog, un bar dimenticato sulla Sunset Strip. I concerti iniziali erano deserti, seguiti da pochi curiosi. Ma Morrison cambiava: la timidezza evaporava, i suoi discorsi si trasformavano in ruggiti rituali, le poesie in trance collettive. Una sera, durante The End, improvvisò un monologo di otto minuti, sprofondando in immagini edipiche, morte e rinascita. Manzarek dirà: “Era come guardare qualcuno aprire la bocca e far uscire l’universo.” Il passaparola fece il resto.

La consacrazione arrivò al Whisky a Go Go, il locale più ambito della Strip. I Doors divennero residenti e ogni sera era una battaglia di energie. Morrison testava i limiti: scalava amplificatori, si spogliava, recitava poesie non previste, insultava o abbracciava il pubblico. Durante l’ultima esibizione, improvvisò una versione oscura e scandalosa di The End. Il proprietario li licenziò. Il giorno dopo, la Elektra offrì loro un contratto discografico.

He spent most of his time in solitude, wandering along Venice Beach, scribbling verses into notebooks, living off cheap food and wine. In 1965, after graduating from UCLA, he drifted away from academic circles. It was on a Venice beach that Ray Manzarek met him and asked what he was doing. Morrison replied that he was writing poetry. When he read a few lines—“Let’s swim to the moon / Let’s climb through the tide…”—Manzarek was struck by the natural musicality of his voice. That’s how The Doors were born. For Morrison, music became the medium to transform his poetry into a collective ritual experience.

They were soon joined by Robby Krieger and John Densmore. Krieger, a gentle-souled guitarist, was influenced by flamenco, blues, and Indian music. Densmore, a jazz drummer, was precise, introspective, and spiritual. The chemistry between the four was immediate. Morrison brought the vision and the voice, like an underground temple; Manzarek the structure, with an organ that became both orchestra and incense; Krieger the emotion, with a liquid, flowing guitar; Densmore the heartbeat, with tribal pulses and jazz syncopations. No band sounded like them.

Their first stage was the London Fog, a forgotten bar on the Sunset Strip. The early shows were empty, attended only by a handful of curious onlookers. But Morrison began to change: his shyness evaporated, his speeches turned into ritual roars, his poems into collective trances. One night, during “The End,” he improvised an eight-minute monologue, plunging into Oedipal imagery, death, and rebirth. Manzarek would later say: “It was like watching someone open their mouth and let the universe pour out.” Word of mouth did the rest.

Their consecration came at the Whisky a Go Go, the most coveted venue on the Strip. The Doors became resident performers, and every night was a battle of energies. Morrison pushed boundaries: climbing amplifiers, stripping down, reciting unscripted poetry, insulting or embracing the audience. During their final performance, he improvised a dark and scandalous version of “The End.” The owner fired them. The next day, Elektra offered them a record deal.

Gli album fondamentali

Ecco una panoramica degli album chiave della band (con Morrison come front-man), ciascuno con un suo contesto, caratteristiche e importanza.

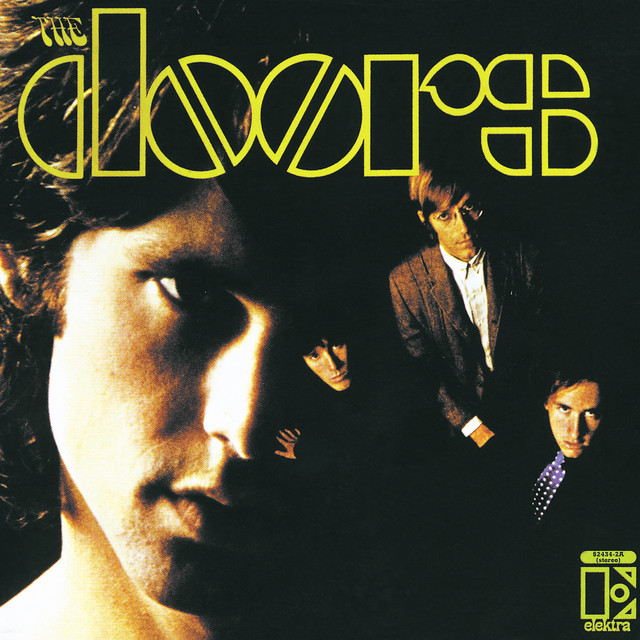

The Doors (1967)

Il debutto omonimo fu pubblicato nel gennaio 1967. Contiene tracce iconiche come “Break On Through (To the Other Side)” e “Light My Fire”.

Il disco si proponeva come “esperienza totale”, un viaggio sonoro che mescolava blues, jazz, psichedelia e poesia. Il brano finale, “The End”, con la sua sezione parlata improvvisata, è diventato leggendario.

Strange Days (1967)

Pubblicato lo stesso anno del debutto, contiene pezzi che esplorano territori ancora più oscuri e sperimentali. Il clima sociale e psicologico degli anni ’60 alimenta contenuti più complessi.

Waiting for the Sun (1968)

Con questo album la band consolida il proprio successo commerciale, pur mantenendo un approccio artistico ambizioso.

The Soft Parade (1969)

Una svolta: si sentono maggiori arrangiamenti orchestrali, sperimentazioni che dividono critica e pubblico.

Morrison Hotel (1970)

Un ritorno al blues più diretto, con canzoni più “terrene” rispetto alle esplorazioni psichedeliche precedenti.

L.A. Woman (1971)

Considerato uno dei vertici della band. Contiene brani come “Riders on the Storm”. Pochi mesi dopo la sua pubblicazione, Morrison morirà.

Here’s an overview of the band’s key albums (with Morrison as frontman), each with its own context, characteristics, and significance.

The Doors (1967)

The self-titled debut was released in January 1967. It features iconic tracks like “Break On Through (To the Other Side)” and “Light My Fire.”

The album was conceived as a “total experience,” a sonic journey blending blues, jazz, psychedelia, and poetry. The final track, “The End,” with its improvised spoken-word section, became legendary.

Strange Days (1967)

Released the same year as the debut, this album delves into even darker and more experimental territory. The social and psychological climate of the 1960s fuels its more complex content.

Waiting for the Sun (1968)

With this album, the band solidified its commercial success while maintaining an ambitious artistic approach.

The Soft Parade (1969)

A turning point: the album features more orchestral arrangements and sonic experimentation, dividing critics and fans alike.

Morrison Hotel (1970)

A return to a more direct blues sound, with songs that feel more grounded compared to the band’s earlier psychedelic explorations.

L.A. Woman (1971)

Considered one of the band’s high points. It includes tracks like “Riders on the Storm.” Just a few months after its release, Morrison would pass away.

Gli ultimi concerti dei Doors: Dallas, New Orleans e il crollo di Jim Morrison

The Doors’ Final Concerts: Dallas, New Orleans, and Jim Morrison’s Collapse

Dopo l’esibizione al Festival dell’Isola di Wight, sul finire del 1970, i Doors decisero di portare avanti ancora due concerti: Dallas e New Orleans. Nessuno poteva immaginare che sarebbero stati gli ultimi live con Jim Morrison.

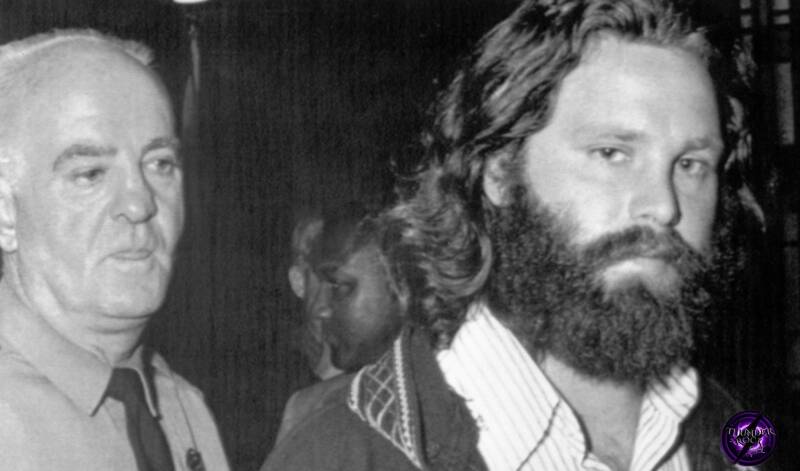

Il clima nella band era teso. Le vicende del processo di Miami gravavano sul morale di Morrison, già da tempo provato da abuso di alcol e stanchezza fisica. A Dallas la situazione apparve instabile ma gestibile; a New Orleans, invece, avvenne l’episodio che segnò la fine definitiva della stagione live del gruppo.

Durante il concerto nella città della Louisiana, Morrison si presentò sul palco visibilmente ubriaco e spossato. Saltava intere strofe, dimenticava versi, arrancava dietro i musicisti. Poi, improvvisamente, crollò: si accasciò contro l’asta del microfono come una marionetta a cui fossero stati tagliati i fili.

Ray Manzarek, ricordando quell’attimo, disse di aver avuto l’impressione che “le energie di Jim si fossero esaurite all’istante”.

L’incidente spinse i Doors a prendere una decisione difficile ma inevitabile: interrompere le esibizioni dal vivo e concentrarsi esclusivamente sul lavoro in studio. Fu in quel periodo che la band completò le registrazioni di L.A. Woman, l’ultimo album con Morrison.

Quelle due ultime date, Dallas e New Orleans, rimasero così l’epilogo doloroso di una delle stagioni più intense della storia del rock.

After their performance at the Isle of Wight Festival in late 1970, The Doors decided to play two more shows: Dallas and New Orleans. No one could have imagined these would be the last live concerts with Jim Morrison.

Tensions within the band were high. The Miami trial weighed heavily on Morrison’s morale, already worn down by alcohol abuse and physical exhaustion. In Dallas, the situation seemed unstable but manageable; in New Orleans, however, an incident occurred that marked the definitive end of the group’s live era.

During the concert in the Louisiana city, Morrison took the stage visibly drunk and depleted. He skipped entire verses, forgot lyrics, and struggled to keep up with the band. Then, suddenly, he collapsed, slumping against the microphone stand like a puppet whose strings had been cut. Ray Manzarek, recalling that moment, said he felt as if “Jim’s energy had drained away instantly.”

The incident led The Doors to make a difficult but inevitable decision: to stop performing live and focus solely on studio work. It was during this period that the band completed the recording of L.A. Woman, the last album with Morrison.

Those final two dates, Dallas and New Orleans, thus became the painful epilogue to one of the most intense chapters in rock history.

Il caso Miami e il rifiuto di Woodstock

Il 1º marzo 1969, durante il concerto a Miami, la crescente dipendenza di Jim Morrison dall’alcol esplose in scena: il cantante fu accusato di atteggiamenti osceni, accuse sempre smentite dai Doors e dal tecnico Vince Treanor, che ricordarono come nessuna delle oltre 430 foto scattate quella sera mostrasse comportamenti indecenti. Nonostante ciò, Morrison finì sotto processo e l’immagine della band subì un duro colpo, portando alla cancellazione di tutti i concerti successivi e incrinando i rapporti con organizzatori e istituzioni.

In quello stesso clima, i Doors rifiutarono di esibirsi al Festival di Woodstock: consideravano l’evento troppo dispersivo e lontano dall’intimità e dall’intensità che cercavano nei loro live. Una scelta oggi sorprendente, ma perfettamente in linea con la loro visione artistica.

The Miami Incident and the Rejection of Woodstock

On March 1, 1969, during a concert in Miami, Jim Morrison’s growing dependence on alcohol erupted on stage: the singer was accused of lewd behavior, charges consistently denied by The Doors and technician Vince Treanor, who pointed out that none of the more than 430 photos taken that night showed any indecent conduct. Nevertheless, Morrison was put on trial, and the band’s image suffered a serious blow, leading to the cancellation of all subsequent concerts and straining relationships with promoters and institutions.

In that same climate, The Doors declined to perform at the Woodstock Festival. They considered the event too chaotic and far removed from the intimacy and intensity they sought in their live shows. A decision that may seem surprising today, but was perfectly aligned with their artistic vision.

“No One Here Gets Out Alive”: la biografia che trasformò Jim Morrison in un’icona eterna

Nel 1980 Jerry Hopkins e Danny Sugerman pubblicarono No One Here Gets Out Alive, la prima biografia completa dedicata a Jim Morrison. Il libro, frutto di anni di interviste, ricerche e testimonianze, divenne rapidamente un bestseller internazionale, contribuendo in modo decisivo alla rinascita del mito dei Doors e del loro enigmatico frontman.

Hopkins, già giornalista di Rolling Stone, aveva iniziato a lavorare all’opera poco dopo la morte di Morrison, ma fu l’intervento di Sugerman , ex assistente della band e profondo conoscitore del mondo dei Doors , a portare a termine il progetto e ad arricchirlo con dettagli, aneddoti e retroscena che catturarono l’immaginazione dei lettori.

“No One Here Gets Out Alive”: The Biography That Turned Jim Morrison into an Eternal Icon

In 1980, Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman published No One Here Gets Out Alive, the first comprehensive biography dedicated to Jim Morrison. The book, the result of years of interviews, research, and firsthand accounts, quickly became an international bestseller, playing a crucial role in reviving the myth of The Doors and their enigmatic frontman.

Hopkins, a former Rolling Stone journalist, began working on the project shortly after Morrison’s death. But it was Sugerman, former assistant to the band and a deep connoisseur of the Doors’ universe, who completed the work, enriching it with vivid details, anecdotes, and behind-the-scenes stories that captured readers’ imaginations.

La biografia non solo riportò l’attenzione sulla musica del gruppo in un periodo di relativo silenzio mediatico, ma contribuì anche a definire l’immaginario moderno attorno a Jim Morrison: poeta maledetto, rockstar autodistruttiva, figura tragica e magnetica. Alcune interpretazioni del libro furono considerate sensazionalistiche da fan e critici, ma ciò non impedì all’opera di diventare un punto di riferimento per generazioni di lettori.

No One Here Gets Out Alive segnò il ritorno dei Doors nella cultura pop e influenzò profondamente l’immagine pubblica di Morrison negli anni successivi, alimentando quel mito che ancora oggi continua a esercitare fascino e mistero.

The biography not only brought renewed attention to the band’s music during a period of relative media silence, but also helped shape the modern mythology surrounding Jim Morrison: the doomed poet, the self-destructive rockstar, a tragic and magnetic figure. Some interpretations of the book were seen as sensationalistic by fans and critics, yet that didn’t stop it from becoming a touchstone for generations of readers.

No One Here Gets Out Alive marked the Doors’ return to pop culture and profoundly influenced Morrison’s public image in the years that followed, fueling a myth that continues to captivate and mystify to this day.

Oliver Stone e “The Doors”: il film che divise pubblico e fan

Nel 1991 il regista Oliver Stone portò sul grande schermo The Doors, un biopic potente e visionario dedicato alla storia della band e alla figura di Jim Morrison. Il film, interpretato da Val Kilmer nei panni del cantante e da Meg Ryan in quelli della sua compagna Pamela Courson, ebbe un forte impatto sulle nuove generazioni: contribuì a riaccendere l’interesse verso la musica del gruppo, riportando i Doors sotto i riflettori della cultura pop a vent’anni dalla morte del loro frontman.

Nonostante il successo di pubblico, la pellicola suscitò un’ondata di critiche da parte dei fan storici e degli stessi membri della band, in particolare Ray Manzarek. Nel suo libro Light My Fire, la mia vita con Jim Morrison, l’ex tastierista descrisse il film di Stone come “un’esagerazione grottesca”, accusando il regista di aver travisato completamente la personalità di Morrison. Secondo Manzarek, il film estremizzava l’immagine del cantante trasformandolo in una sorta di “superuomo nietzschiano”, fino a sfiorare rappresentazioni che, a suo dire, lo avvicinavano ingiustamente a una figura autoritaria o addirittura fascistoide.

Manzarek si spinse oltre, criticando Stone per una presunta lettura distorta dei temi filosofici cari a Morrison e accusandolo di un “latente antisemitismo”, un’accusa che contribuì a rendere ancora più teso il rapporto tra la band e il film.

Oggi The Doors rimane un’opera controversa: artisticamente audace, carica dell’energia tipica del cinema di Stone, ma contestata per il suo approccio drammatico e romanzato. Un film che, nel bene e nel male, continua a far discutere e a riaccendere l’interesse per una delle band più iconiche degli anni ’60.

Oliver Stone and The Doors: The Film That Divided Audiences and Fans

In 1991, director Oliver Stone brought The Doors to the big screen, a powerful, visionary biopic dedicated to the band’s story and the figure of Jim Morrison. The film, starring Val Kilmer as the singer and Meg Ryan as his partner Pamela Courson, had a strong impact on younger generations. It helped reignite interest in the band’s music, bringing The Doors back into the spotlight of pop culture twenty years after their frontman’s death.

Despite its commercial success, the film sparked a wave of criticism from longtime fans and even members of the band, particularly Ray Manzarek. In his book Light My Fire: My Life with Jim Morrison, the former keyboardist described Stone’s film as “a grotesque exaggeration,” accusing the director of completely misrepresenting Morrison’s personality. According to Manzarek, the film exaggerated the singer’s image, turning him into a kind of “Nietzschean superman,” bordering on portrayals that, in his view, unfairly aligned Morrison with authoritarian or even fascist traits.

Manzarek went further, criticizing Stone for a supposedly distorted interpretation of the philosophical themes dear to Morrison and accusing him of “latent antisemitism”, a charge that further strained the relationship between the band and the film.

Today, The Doors remains a controversial work: artistically bold, infused with the raw energy typical of Stone’s cinema, yet contested for its dramatic and fictionalized approach. A film that, for better or worse, continues to spark debate and renew interest in one of the most iconic bands of the 1960s.

L’ultimo viaggio

A Parigi ritrovò Pamela Courson, l’amore e il tormento di una vita. Scriveva poesie, camminava a lungo, cercava di smettere di bere. Guardava la Senna per ore, diceva di sentirsi finalmente libero. Ma i fantasmi non lo avevano mai veramente lasciato. Nella notte del 3 luglio 1971, il suo cuore decise di fermarsi. Aveva 27 anni. La causa ufficiale fu arresto cardiaco, senza autopsia. Le circostanze, mai chiarite del tutto, alimentarono leggende e speculazioni.

Morrison venne sepolto al cimitero di Père-Lachaise, accanto ai poeti che aveva amato. La sua tomba è oggi meta di pellegrinaggio: fiori, versi, lettere, piccoli doni portati da chi non l’ha mai conosciuto ma lo sente ancora vivo.

Oltre alla musica, Morrison pubblicò raccolte di poesie come The Lords and The New Creatures e An American Prayer (postumo, con la band). Il suo stile poetico univa mitologia e simbolismo, flusso di coscienza, erotismo metafisico, critica sociale e ricerca del sublime tramite l’eccesso. Vedeva nella poesia una forma di catarsi, un modo per attraversare le ombre dell’inconscio e tornare trasformati.

Pamela fu la sua regina, musa e compagna cosmica. La loro relazione, tormentata e intensa, fu il riflesso di un legame emotivo e artistico profondo.

Dopo la sua morte, Manzarek, Krieger e Densmore capirono di aver perso qualcosa di più di un cantante: avevano perso un’alchimia irripetibile. La storia dei Doors non finì. Continuò come mito, come libro, come film, come pellegrinaggio alla tomba di Père-Lachaise.

La loro musica rimane un portale. Chiunque ascolti The End o Riders on the Storm entra per un attimo in quel mondo sospeso, sensuale, pericoloso, misterioso. Una porta aperta tra ciò che siamo e ciò che vorremmo essere.

I Doors non furono semplicemente una band. Furono un esperimento artistico e spirituale, una collisione tra poesia e suono, tra visione e ribellione. Jim Morrison non fu solo un frontman: fu un simbolo, un archetipo, una ferita aperta nella storia del rock.

La sua voce continua a parlarci. I suoi versi continuano a inquietarci. La sua assenza continua a bruciare.

La loro storia è il riflesso di un’epoca. E di un’urgenza che ancora oggi risuona.

The Final Journey

In Paris, he reunited with Pamela Courson, the love and torment of his life. He wrote poetry, walked for hours, tried to stop drinking. He would gaze at the Seine for long stretches, saying he finally felt free. But the ghosts had never truly left him. On the night of July 3, 1971, his heart decided to stop. He was 27. The official cause was cardiac arrest, with no autopsy. The circumstances, never fully clarified, fueled legends and speculation.

Morrison was buried in Père-Lachaise Cemetery, among the poets he had loved. His grave is now a place of pilgrimage: flowers, verses, letters, small offerings brought by those who never knew him but still feel him alive.

Beyond music, Morrison published poetry collections such as The Lords and The New Creatures and An American Prayer (posthumously, with the band). His poetic style fused mythology and symbolism, stream of consciousness, metaphysical eroticism, social critique, and a search for the sublime through excess. He saw poetry as a form of catharsis, a way to pass through the shadows of the unconscious and emerge transformed.

Pamela was his queen, muse, and cosmic companion. Their relationship, intense and troubled, reflected a deep emotional and artistic bond.

After his death, Manzarek, Krieger, and Densmore realized they had lost more than a singer, they had lost an unrepeatable alchemy. The story of The Doors didn’t end. It continued as myth, as book, as film, as pilgrimage to Père-Lachaise.

Their music remains a portal. Anyone who listens to The End or Riders on the Storm steps for a moment into that suspended world, sensual, dangerous, mysterious. A door opened between who we are and who we long to be.

The Doors were not simply a band. They were an artistic and spiritual experiment, a collision of poetry and sound, of vision and rebellion. Jim Morrison was not just a frontman: he was a symbol, an archetype, an open wound in the history of rock.

His voice still speaks to us. His verses still unsettle us. His absence still burns.

Their story is the reflection of an era. And of an urgency that still resonates today.

Aggiungi commento

Commenti